How legal protections shape access to learning in Africa

"There is no tool for development more effective than the empowerment of women and nothing empowers more than education." — Kofi Annan, former UN Secretary General1

Education is recognized as a cornerstone for societal progress, especially in African nations, where it plays a vital role in driving development. The right to education is fundamental for fostering a civilized, peaceful and inclusive society free from discrimination. While education is often seen as an investment in the younger generation, particularly children and youth, it is equally important for adults, who must be encouraged to engage in lifelong learning. Viewed as a key factor in personal growth, education also contributes to the development of a prosperous and economically strong nation where all citizens share in the country's overall progress. The primary aim of educational policies in any nation is to guarantee the right to education for all its citizens and ensure that everyone has access to a sufficient level of education to thrive.

In this context access to education is a fundamental right , universally acknowledged and protected by laws, constitutions and international conventions. For example in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) article 23 declares that : “Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit2”.

1Secretary General Kofi Annan’s keynote address to the annual gala event of the International Women’s Health Coalition, in New York on 15 January 2004.

2United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 26(1), available at: https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/.

Another example is the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, article 17 : “Every individual shall have the right to education. Every people shall have the right to education and to freely pursue its self-development in the context of a democratic society3”.

Despite the strong legal framework supporting education as a fundamental right, access to education remains a significant challenge in many parts of the world, particularly in African countries. Factors such as poverty, gender inequality, conflict and inadequate infrastructure often prevent children and adults from benefiting fully from educational opportunities. This gap in access undermines the potential for social and economic development and hinders progress toward creating an equitable society.

The problem is not only about the availability of education but also about the quality and inclusivity of the education provided. Laws and international conventions recognize the importance of education, but they must be actively enforced and adapted to the local context to address the specific barriers preventing access to education for all children, particularly in marginalized communities.

The following sections will explore how laws and legislation can serve as the key drivers to ensure that the right to education is not merely theoretical but a reality for every child. First, we will examine how the right to education is protected in African countries and the legal mechanisms in place. Then, we will discuss how laws can combat discrimination in education, ensuring that every child, regardless of gender, background, or socioeconomic status, has the opportunity to learn and grow. Finally, we will offer recommendations for strengthening the enforcement of education rights and share how our NGO is actively working to help make education accessible to children, despite the challenges.

3Organization of African Unity, African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, Article 17(1), available at: https://www.achpr.org/legalinstruments/detail?id=49.

1. The Barriers to Educational Access in Africa

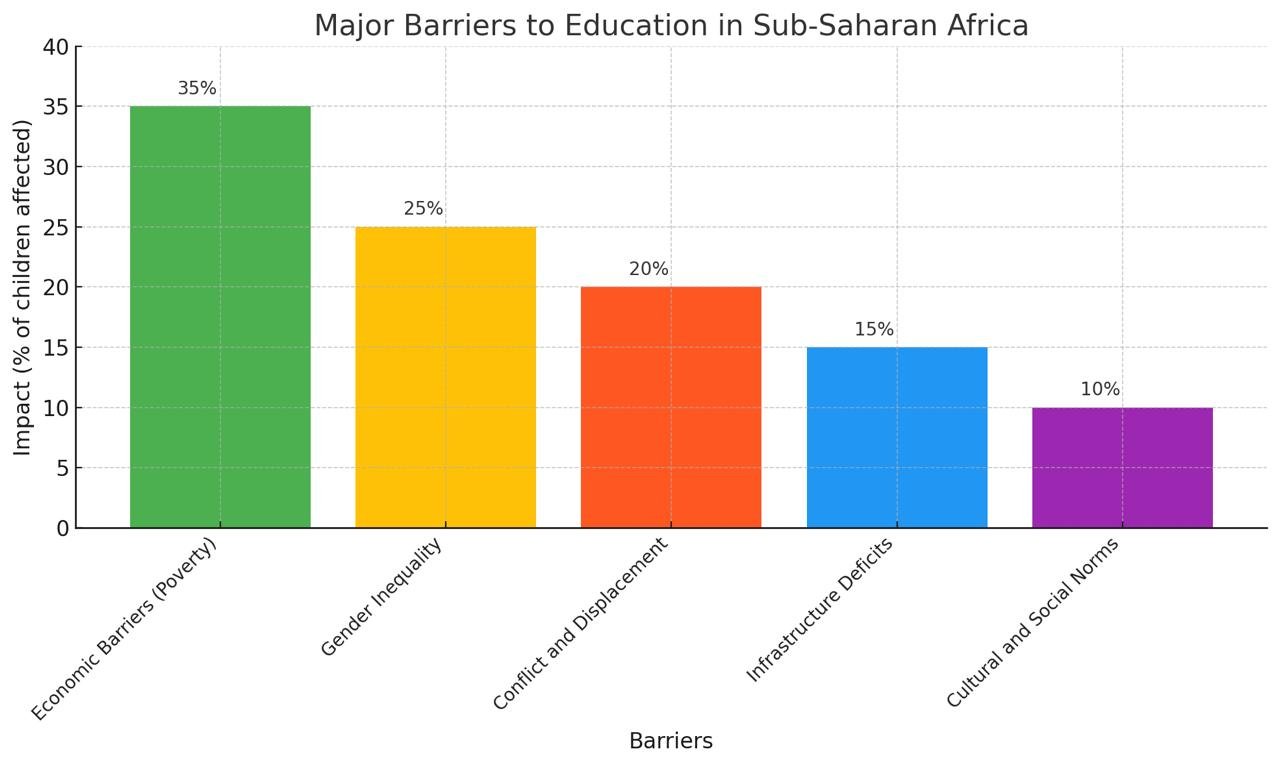

This chart represents the major barriers to education in sub-Saharan Africa. The chart illustrates the percentage of children impacted by different obstacles, making it easier to grasp the relative scale of each issue:

A. Economic Barriers (Poverty and Child Labor): 45%

Poverty remains the most significant barrier to education in sub-Saharan Africa, affecting over 40% of school-aged children4. Families living below the poverty line often prioritize immediate survival over long-term benefits like education. As a result, many children are forced to engage in child labor to supplement household income.

In Nigeria, for instance, it is estimated that 43% of children aged 5 to 14 are engaged in some form of child labor 5 . These children miss out on essential early education, perpetuating a cycle of poverty and illiteracy. A UNESCO study highlights that providing financial incentives such as conditional cash transfers can reduce the dropout rate by 20%, emphasizing the need for targeted government interventions.

Moreover, hidden costs of "free education," such as uniforms, textbooks and exam fees, create an additional burden on low-income families. Studies show that eliminating these costs could increase enrollment rates by up to 15% in rural areas 6.

Case Study 1: Nigeria – Economic Barriers and Child Labor

Nigeria faces a severe education crisis with 8.7 million children out of school, the highest number globally. Economic hardships, exacerbated by widespread poverty, compel children to work instead of attending school. Many families cannot afford tuition, uniforms, or textbooks due to Nigeria's reliance on informal economies and lack of universal free education enforcement.

4UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report (2022), Monitoring Education Challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa.accessed on november 14 , 2024

5International Labor Organization Report (2023), Global Estimates on Child Labor: Trends and Impacts. accessed 14 , november 2024

6World Bank (2023), "Education Statistics in Africa: Addressing Barriers to Learning," available at https://www.worldbank.org, accessed on November 15, 2024

In northern Nigeria, cultural norms and economic constraints amplify gender disparities. Initiatives like the Girls’ Education Project (GEP3), supported by UNICEF and the UK Government, aim to enroll more girls in schools by reducing costs and addressing cultural barriers. However, success is slow, with high dropout rates persisting among rural and low-income communities78.

B. Gender Disparities: 23%

Gender inequality is a pervasive issue in education, especially in regions where cultural norms and traditional practices prioritize boys' education over girls'. According to UNICEF, 9 million girls of primary school age will never set foot in a classroom, compared to 6 million boys.

In countries like Kenya and Mali, early marriage is a significant barrier. Approximately 23% of girls in sub-Saharan Africa are married before the age of 18, leading to a sharp decline in school attendance . Girls also face additional challenges such as inadequate sanitation facilities, which deter them from attending school during menstruation.

Programs like the Let Girls Learn initiative, launched by international donors, have demonstrated success in addressing these challenges by building gender-sensitive schools and providing menstrual hygiene kits. However, entrenched cultural resistance continues to hinder progress9.

7UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report (2022): https://uis.unesco.org/ accessed on 15 November 2024.

8UNICEF Reports on Education and Gender Disparities https://www.unicef.org/education/girls-education#:~:text=Worldwide%2C%20119%20million%20girls%20are,cent%20in%20upper%20secondary%20education. accessed on 15 November 2024.

9UNICEF (2023), "Gender Disparities in Education: The State of Girls’ Education," available at https://www.unicef.org/reports, accessed on November 15, 2024.

Case Study 2 : Kenya – Gender Disparities

In rural areas like Turkana County, girls face significant obstacles to accessing education due to early marriages, traditional roles and inadequate school facilities. Despite national policies like the Basic Education Act (2013), which mandates free and compulsory primary education, enforcement remains weak in pastoralist regions.

Projects such as WINGS to Fly by Equity Group Foundation and partners like the Mastercard Foundation have had notable impacts, offering scholarships to girls from marginalized areas. Yet, rural schools continue to struggle with high teacher-pupil ratios (often exceeding 1:60) and cultural resistance to female education10.

C. Conflict and Displacement: 35%

Armed conflicts have left over 2.2 million children out of school in South Sudan alone11. Conflict destroys educational infrastructure, displaces families and disrupts learning for years. Refugee children often face overcrowded classrooms, limited resources and psychological trauma, further impairing their ability to learn.

A poignant example is the Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya, where over 50% of school-aged children lack access to formal education12. Emergency education programs funded by the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) have helped establish temporary learning spaces, but these solutions remain underfunded and unsustainable in the long term.

10UNICEF Reports on Education and Gender Disparities https://www.unicef.org/education/girls-education#:~:text=Worldwide%2C%20119%20million%20girls%20are,cent%20in%20upper%20secondary%20education. accessed on the 15 November 2024.

11Save the Children (2022), "Education in Conflict Zones: Protecting the Future of Children," available at https://www.savethechildren.org, accessed on November 15, 2024.

12UNHCR (2023), "Kakuma Refugee Camp and Education Access," available at https://www.unhcr.org, accessed on November 16, 2024.

The ripple effects of conflict are far-reaching: regions affected by war experience a decline in teacher availability, as many educators flee for safety. A study by UNESCO found that conflict zones have 30% fewer qualified teachers compared to peaceful areas.

Case Study 2: South Sudan – Conflict and Displacement

South Sudan is one of the most conflict-affected countries globally, with over 2.2 million children out of school. Years of civil war have destroyed school infrastructure and displaced families, disrupting educational access. Refugee children living in camps, such as those in Uganda or Kenya, face additional hurdles like overcrowding and lack of teaching materials.

Efforts by NGOs like Save the Children have provided temporary learning spaces, but resources remain inadequate. In 2022, the organization noted that only 50% of schools in conflict zones were operational, leaving millions without formal education13.

13Save the Children – Reports on Conflict and Education in South Sudan https://www.savethechildren.org/

2. Legislative Foundations for Securing the Right to Education

Education is universally recognized as a fundamental right and is safeguarded by a combination of national constitutions, international treaties and regional charters. Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) affirms that “everyone has the right to education,” emphasizing free and compulsory elementary education as a foundation for societal advancement. Similarly, the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC) obliges member states to take measures to ensure the provision of free and accessible education for all children, reflecting a continental commitment to the right to learn. Nationally, countries like South Africa have enshrined the right to education within their constitutions; Section 29 of the South African Constitution, for example, guarantees the right to basic education for every citizen, placing the onus on the government to ensure equal access.

Legal scholars argue that these legislative frameworks form the backbone of educational equity. According to Tomasevski's Analysis of the Right to Education, the success of such laws depends heavily on their enforcement mechanisms, such as monitoring by independent bodies or human rights commissions. However, enforcement remains uneven across Africa. Studies show that while 90% of African countries have ratified key education-related conventions, only 45% have implemented policies that align with these commitments effectively.

International organizations like UNICEF and UNESCO have emphasized that legislation must go beyond mere recognition to ensure practical outcomes. For instance, UNICEF recommends integrating laws with financial mechanisms, such as free school meal programs and transportation subsidies, to remove indirect barriers to education.

Similarly, UNESCO advocates for the incorporation of anti-discrimination clauses in education laws to address gender-based inequities.

A. Recommendations from International Frameworks

- UNESCO's Education 2023 Framework for action suggests that African governments adopt inclusive education policies, particularly for marginalized groups such as girls and refugees. These policies should be accompanied by actionable targets, such as achieving gender parity in enrollment by 2030.

- UNICEF proposes mandatory data collection to monitor compliance with education rights laws and to identify gaps in accessibility. For example, real-time data on school attendance can highlight areas where laws are not effectively implemented.

- The Global Partnership for Education (GPE) highlights the need for harmonizing international commitments with national education budgets, ensuring that a minimum of 20% of public expenditure is allocated to the education sector.

B. Scholarly Perspectives and Legislative Gaps

Authors like Katarina Tomasevski and Manfred Nowak critique the tendency of governments to use laws as symbolic gestures without ensuring their enforceability. In The Right to Education: Law and Policy, Tomasevski argues that many African nations suffer from a disconnect between legal provisions and actionable policies. For example, while Kenya’s Basic Education Act mandates free education, schools often lack sufficient funding, leading to hidden costs that undermine accessibility.

Dr. Sohail Inayatullah, in his analysis of future-oriented education laws, highlights the importance of aligning legal frameworks with emerging challenges like digital inclusion. He suggests that future education laws in Africa must address disparities in access to technology, particularly as e-learning becomes a critical tool in modern education delivery.

3. NJO Foundation Africa: Bridging the Gaps Where Legislation Falls Short to Empower Communities

In many African nations, the laws meant to protect children and support their education often lack the necessary resources and infrastructure for effective implementation. For example, many children in rural areas face barriers such as unaffordable school fees, lack of teaching materials and poor sanitary conditions that prevent them from attending school regularly. While international agreements recognize education as a fundamental right, the legislative frameworks within some African countries struggle to provide adequate support due to limited budgets and political instability.

This is where the NJO Foundation Africa plays a crucial role. By funding and managing projects that directly address these gaps, the foundation empowers children to access education, provides critical healthcare services and promotes social welfare for the elderly and marginalized groups. For instance, the foundation’s sanitary pads initiative helps keep girls in school, eliminating a major reason for absenteeism due to menstruation. Similarly, its outreach programs focus on skills development, healthcare access and sustainable livelihoods, which support economic independence and community resilience.

Given that legislative frameworks in many African nations remain weak or unenforced, funding organizations like the NJO Foundation Africa is vital. Their work ensures that children receive the education and healthcare they deserve, regardless of governmental shortcomings. Donations to such foundations directly contribute to the long-term development of African communities, creating sustainable change in places where legislative interventions may be delayed or ineffective. The foundation not only addresses immediate needs but also fosters systemic change through community empowerment and development programs, which ultimately create a cycle of self-sufficiency and progress.

By supporting organizations like NJO Foundation Africa, we can mitigate the effects of weak legislation and ensure that more children and families have the opportunities they need to thrive.